The nuclear weapons tests of the United States were performed from 1945 to 1992 as part of the nuclear arms race. The United States conducted around 1,054 nuclear tests by official count, including 216 atmospheric, underwater, and space tests. Most of the tests took place at the Nevada Test Site (NNSS/NTS) and the Pacific Proving Grounds in the Marshall Islands and off Kiritimati Island in the Pacific, plus three in the Atlantic Ocean. Ten other tests took place at various locations in the United States, including Alaska, Nevada other than the NNSS/NTS, Colorado, Mississippi, and New Mexico. (via Wikipedia)

The Nevada National Security Site, known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles northwest of the city of Las Vegas.

The Nevada National Security Site, known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles northwest of the city of Las Vegas.

Formerly known as the Nevada Proving Grounds, the site was established in 1951 for the testing of nuclear devices. It covers approximately 1,360 square miles of desert and mountainous terrain. Nuclear weapons testing at the site began with a 1-kiloton-of-TNT bomb dropped on Frenchman Flat on January 27, 1951. Over the subsequent four decades, over 1,000 nuclear explosions were detonated at the site. Many of the iconic images of the nuclear era come from the site.

During the 1950s, the mushroom clouds from the 100 atmospheric tests could be seen from almost 100 miles away. The city of Las Vegas experienced noticeable seismic effects, and the mushroom clouds, which could be seen from the downtown hotels, became tourist attractions. Westerly winds routinely carried the fallout from above-ground nuclear testing directly through St. George, Utah and southern Utah. Increases in cancers, such as leukemia, lymphoma, thyroid cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, bone cancer, brain tumors, and gastrointestinal tract cancers, were reported from the mid-1950s onward. A further 828 nuclear tests were carried out underground.

Nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll consisted of the detonation of 23 nuclear weapons by the United States between 1946 and 1958 on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Tests occurred at 7 test sites on the reef itself, on the sea, in the air, and underwater. The test weapons produced a combined fission yield of 42.2 Mt of TNT in explosive power.

Nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll consisted of the detonation of 23 nuclear weapons by the United States between 1946 and 1958 on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Tests occurred at 7 test sites on the reef itself, on the sea, in the air, and underwater. The test weapons produced a combined fission yield of 42.2 Mt of TNT in explosive power.

The United States and its allies were engaged in a Cold War nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union to build more advanced bombs from 1947 until 1991. The first series of tests over Bikini Atoll in July 1946 was codenamed Operation Crossroads. Able was dropped from an aircraft and detonated 520 ft above the target fleet. The second, Baker, was suspended under a barge. It produced a large Wilson cloud and contaminated all of the target ships. Chemist Glenn T. Seaborg, the longest-serving chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, called the second test "the world's first nuclear disaster."

The second series of tests in 1954 was codenamed Operation Castle. The first detonation was Castle Bravo, which tested a new design utilizing a dry-fuel thermonuclear bomb. It was detonated at dawn on March 1, 1954. Scientists miscalculated: the 15 Mt of TNT nuclear explosion far exceeded the expected yield of 4–8 Mt of TNT. This was about 1,000 times more powerful than either of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. The scientists and military authorities were shocked by the size of the explosion, and many of the instruments that they had put in place to evaluate the effectiveness of the weapon were destroyed.

Authorities had promised the Bikini Atoll's residents that they would be able to return home after the nuclear tests. A majority of the island's family heads agreed to leave the island, and most of the residents were moved to the Rongerik Atoll and later to Kili Island. Both locations proved unsuitable to sustaining life, and the United States had to provide residents with on-going aid. Despite the promises made by authorities, these and further nuclear tests rendered Bikini unfit for habitation, contaminating the soil and water, making subsistence farming and fishing too dangerous. The United States later paid the islanders and their descendants $125 million in compensation for damage caused by the nuclear testing program and their displacement from their home island. A 2016 investigation found radiation levels on Bikini Atoll as high as 639 mrem yr−1, well above the established safety standard for habitation.

After the end of World War II, Enewetak came under the control of the United States as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, until the independence of the Marshall Islands in 1986. During its tenure, the United States evacuated the local residents many times, often involuntarily. The atoll was used for nuclear testing, as part of the Pacific Proving Grounds. Before testing commenced, the U.S. exhumed the bodies of United States servicemen killed in the Battle of Enewetak and returned them to the United States to be re-buried by their families. 43 nuclear tests were fired at Enewetak from 1948 to 1958.

After the end of World War II, Enewetak came under the control of the United States as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, until the independence of the Marshall Islands in 1986. During its tenure, the United States evacuated the local residents many times, often involuntarily. The atoll was used for nuclear testing, as part of the Pacific Proving Grounds. Before testing commenced, the U.S. exhumed the bodies of United States servicemen killed in the Battle of Enewetak and returned them to the United States to be re-buried by their families. 43 nuclear tests were fired at Enewetak from 1948 to 1958.

The first hydrogen bomb test, code-named Ivy Mike, occurred in late 1952 as part of Operation Ivy; it vaporized the islet of Elugelab. This test included B-17 Flying Fortress drones to fly through the radioactive cloud to test onboard samples. B-17 mother ships controlled the drones while flying within visual distance of them. In all, 16 to 20 B-17s took part in this operation, of which half were controlling aircraft and half were drones. To examine the explosion clouds of the nuclear bombs in 1957/58, several rockets (mostly from rockoons) were launched. One USAF airman Jimmy Robinson was lost at sea during the tests. Robinson's F-84 Thunderjet crashed and sank 3.5 miles short of the island. Robinson's body was never recovered.

A radiological survey of Enewetak was conducted from 1972 to 1973. In 1977, the United States military began decontamination of Enewetak and other islands. During the three-year, US$100 million cleanup process, the military mixed more than 80,000 cubic meters of contaminated soil and debris from the islands with Portland cement and buried it in an atomic blast crater on the northern end of the atoll's Runit Island. The material was placed in the 9.1-meter deep, 110-meter wide crater created by the May 5, 1958, "Cactus" nuclear weapons test. A dome composed of 358 concrete panels, each 46 centimeters thick, was constructed over the material. The final cost of the cleanup project was US$239 million. The United States government declared the southern and western islands in the atoll safe for habitation in 1980, and residents of Enewetak returned that same year. The military members who participated in that cleanup mission are suffering from many health issues, but the U.S. Government is refused to provide health coverage until 2022 with the passage of the PACT Act.

Section 177 of the 1983 Compact of Free Association between the governments of the United States and the Marshall Islands establishes a process for Marshallese to make a claim against the United States government as a result of damage and injury caused by nuclear testing. That same year, an agreement was signed to implement Section 177, which established a US$150 million trust fund. The fund was intended to generate US$18 million a year, which would be payable to claimants on an agreed-upon schedule. If the US$18 million a year generated by the fund was not enough to cover claims, the principal of the fund could be used. A Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal was established to adjudicate claims. In 2000, the tribunal made a compensation award to the people of Enewetak consisting of US$107.8 million for environmental restoration; US$244 million in damages to cover economic losses caused by loss of access and use of the atoll; and US$34 million for hardship and suffering.[30] In addition, as of the end of 2008, another US$96.658 million in individual damage awards were made. Only US$73.526 million of the individual claims award has been paid, however, and no new awards were made between the end of 2008 and May 2010. Due to stock market losses, payments rates that have outstripped fund income, and other issues, the fund was nearly exhausted, as of May 2010, and unable to make any additional awards or payments. A lawsuit by Marshallese arguing that "changed circumstances" made Nuclear Claims Tribunal unable to make just compensation was dismissed by the Supreme Court of the United States in April 2010.

The 2000 environmental restoration award included funds for additional cleanup of radioactivity on Enewetak. Rather than scrape the topsoil off, replace it with clean topsoil, and create another radioactive waste repository dome at some site on the atoll (a project estimated to cost US$947 million), most areas still contaminated on Enewetak were treated with potassium.[32] Soil that could not be effectively treated for human use was removed and used as fill for a causeway connecting the two main islands of the atoll (Enewetak and Parry). The cost of the potassium decontamination project was US$103.3 million.

A report by the US Congressional Research Service projects that the majority of the atoll will be fit for human habitation by 2026–2027, after nuclear decay, de-contamination and environmental remediation efforts create sufficient dose reductions. However, in November 2017, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported that rising sea levels caused by climate change are seeping inside the dome, causing radioactive material to leak out.

Nuclear tests were conducted on and around Kiritimati by the United Kingdom in the late 1950s, and by the United States in 1962. During these tests, the island was not evacuated, exposing the i-Kiribati residents and the British, New Zealand, and Fijian servicemen to nuclear radiation.

Nuclear tests were conducted on and around Kiritimati by the United Kingdom in the late 1950s, and by the United States in 1962. During these tests, the island was not evacuated, exposing the i-Kiribati residents and the British, New Zealand, and Fijian servicemen to nuclear radiation.

The entire island is a Wildlife Sanctuary; access to five particularly sensitive areas is restricted.

During the Cold War Kiritimati was used for nuclear weapons testing by the United Kingdom and the USA.

The United States also conducted 22 successful nuclear detonations over the island as part of Operation Dominic in 1962. Some toponyms (like Banana and Main Camp) come from the nuclear testing period, during which at times over 4,000 servicemen were present. By 1969, military interest in Kiritimati had ended and the facilities were mostly dismantled. However, some communications, transport, and logistics facilities were converted for civilian use, which Kiritimati uses to serve as the administrative centre for the Line Islands.

There is no reliable data on the environmental and public health impact of the nuclear tests conducted on the island in the late 1950s. A 1975 study claimed that there was negligible radiation hazard; certainly, fallout was successfully minimised. More recently however, a Massey University study of New Zealand found chromosomal translocations to be increased about threefold on average in veterans who participated in the tests; most of the relevant data remains classified to date.

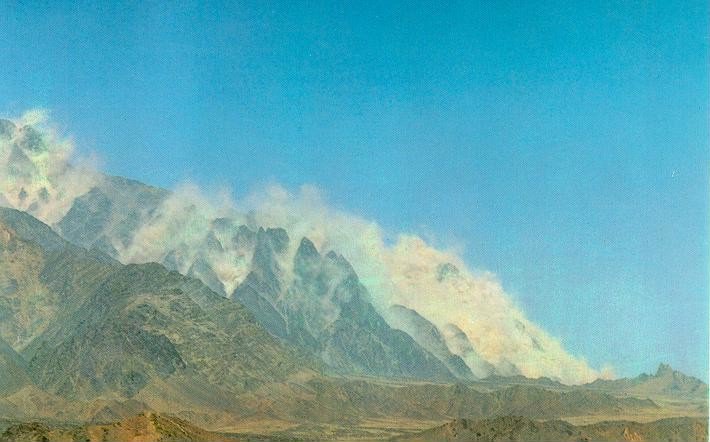

Chagai-I is the code name of five simultaneous underground nuclear tests conducted by Pakistan at 15:15 hrs PKT on 28 May 1998. The tests were performed at Ras Koh Hills in the Chagai District of Balochistan Province.

Chagai-I is the code name of five simultaneous underground nuclear tests conducted by Pakistan at 15:15 hrs PKT on 28 May 1998. The tests were performed at Ras Koh Hills in the Chagai District of Balochistan Province.

Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site (풍계리 핵 실험장) was the only known nuclear test site of North Korea. Nuclear tests were conducted at the site in October 2006, May 2009, February 2013, January 2016, September 2016, and September 2017.

Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site (풍계리 핵 실험장) was the only known nuclear test site of North Korea. Nuclear tests were conducted at the site in October 2006, May 2009, February 2013, January 2016, September 2016, and September 2017.